Browse Exhibits (2 total)

Click To Accept: Examining Terms of Use, Privacy Policies, and Data Collection Policies

“...if the smartphone is becoming a de facto necessity, it is at the same time impossible to use the device as intended without, in turn, surrendering data to it and the network beyond.” (Greenfield 2017, 25)

Therein lies the problem: the things we need to live, work, play, and be in our 21st century digital world are (potentially, if not yet fully actual) weapons of mass deduction and deception. They collect our consent even if we don’t even realize it, our data even if we aren’t sure what that consists of, and our attention even if that is manipulated in ways invisible to our human eyes. In the Introduction to Radical Technologies, The Design of Everyday Life, Adam Greenfield (2017) paints a picture of contemporary Paris in which every human activity is captured and logged by the digital technologies ubiquitous in any large 21st century city. He notes that, from this trove of data, “Latent patterns and unexpected correlations can be identified, in turn suggesting points of effective intervention to those with a mind to exert control” (2).

We are not unaware that this is happening. We know that our devices and technologies are collecting information and permitting certain uses (and prohibiting others). We know that we are surrendering our personal information to applications that allow us the convenience of paying our bills digitally, of keeping in touch with our buddies from college, of composing documents and storing them in cloud servers. We know this because our devices, platforms, applications, and software tell us so in the various End User License Agreements, and Data Collection Policies, and Privacy Policies, and Terms of Service that we’re presented with each time we install a new app or update to the latest OS or join a social media platform or make an online purchase. They are telling us exactly what is what in no uncertain legal terms, even if the wording is confusing. But are we listening? Do we read the fine print before we “click here” to agree to the terms? And even if we do read it, do we really know what we’re agreeing to get ourselves into?

These are the questions that we want to engage with in this exhibit, Click to Accept: Examining Terms of Use, Privacy Policies, and Data Collection Policies, created as part of our work in Writing for the Web, an upper level English class at the University of Georgia in Fall 2018. This semester, we have focused on data and algorithms as the central features of the digital networked environment - features that inevitably impact the composition, circulation, and receptions of texts. Our course description notes,

“These days our experience of the world wide web is shaped by algorithms and captured in data. Wherever we go online, whatever we do, algorithms affect what information we receive and the applications and platforms we use are collecting data about our online habits and activities and we are contributing content (e.g., tweets, Reddit posts, etc.) that researchers can use to explore new questions and solve complex problems. But data and algorithms can be misused. Even people for whom data is not intended can take advantage of users’ information; we are not always aware of how much of ourselves we share. Outside of places like Facebook, third-party sites exist purely for the purpose of tracking people and finding information from addresses to arrest records. They can misrepresent and manipulate and be manipulated in ways that have profound and wide-ranging effects. In this course, we will investigate the ways that writers and writing are evolving in the face of new challenges for textual composition/design, information management, and writing for and with readers that may be machines as well as humans.”

We have also been inspired by a Call for Proposals for a special issue of Computers and Composition, "Rhetorics of Data: Collections, Consent, & Critical Digital Literacies." In that call, guest editors Les Hutchinson and Maria Novotny ask scholars to consider “rhetorical action in regard to ethical questions about data collection, consent, and the need to acquire critical digital literacies as response.” In order to better understand the ethical and legal landscape that users of digital technologies and media encounter, we decided to collect and analyze examples of various policies, paying particular attention to how their rhetoric affects user understanding.

In this exhibit, we present to you examples of policies that articulate the rights and responsibilities of both users and providers of various digital services. In compiling this collection, we have learned a few things about their rhetoric, implications for writers of such policies, and the critical digital literacies that we must cultivate to be truly informed citizens of the digital age. Check out the pages on the right for more of our ideas and then browse the three collections (Data Collection Policies, Privacy Policies, and EULAs and Terms of Service). We hope this exhibit makes you think twice before you just "click to accept"!

Writing for the Web, Fall 2018

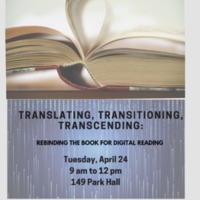

Translating, Transitioning, Transcending: Rebinding the Book for Digital Reading

This semester (Spring 2018) in Writing for the World Wide Web, we are stepping back into the history of reading and writing in order to develop innovative solutions for the problems associated with reading onscreen. Our challenge as writers for the online, networked digital environment is to engage readers who are faced with several critical obstacles - that we articulate here as TMI, tl;dr, and Tech Rage - to close, careful, "deep" reading, as well as our own difficulties in working with/in a medium that is, if no longer "new," then certainly still "immature" (per Janet Murray).

So, in this exhibit, we'd like to show you how we took a unique approach to writing for the web by exploring material from the Hargrett Rare Book and Manuscript Collection in the University of Georgia's Special Collections Libraries. We also had the chance to visit the Digital Arts Library (also currently housed in the Special Collections Libraries) and were inspired by some of the early experiments in electronic literature and interactive narrative and video games in that collection. Our goal was to find inspiration for innovative, creative design thinking about textual form and experience.

In this exhibit, we will show you the texts that inspired us to create our own digital textual design concepts and plans. We invite you to browse through the collections herein and take a look at the texts that provoked our imaginations. But first, take a look at the pages on the right to understand the three main ideas behind this project and why we think that, in order to design the digital future, it might be necessary to think more about the past, about craft, and about the pleasure of the text.